Reducing one's bodyweight affect the Press tremendously, and I calculate it takes me four months to rebuild my Press back to normal. Having reduced about 10 times in the last two years, I feel I have not had a fair chance to improve my press outstandingly. Therefore, because I

despite the handicap mentioned, I have no qualms in recommending the following special exercises to anyone having difficulty in progressing, especially those who appear to have reached a sticking-point in poundage.

take a lot out of a man, and so advise lifters to use these "Assistance Exercises" on alternate nights from ordinary training. Some advice on schedules containing assistance exercises will be found in an ensuing chapter.

This is an exercise to strengthen the chief muscles used in the Press, and is little different from the orthodox movement, except that -- being performed seated -- it does not allow for any back-bend, and consequently assists in strengthening the back to a great degree. A bench is the best thing to sit on, being the correct height; but no matter what you decide to use it is important that the thighs be at the requisite height when seated.

Take hold of the bar, first ensuring the bench or box is in a position immediately behind, so that no energy is wasted in getting seated with the bar. Pull in to the shoulders in the usual way and sit down naturally. This exercise can be made easier by sitting on the edge of the bench, but when made easier that way it loses some of its benefits.

Keeping the eyes fixed on a spot just over eye-level ahead, press in the usual fashion.

4 sets of 4 reps with 40 lbs below actual maximum pressing capacity.

It will be noticed in all exercises that, where poundages are concerned, only such approximations can be given. It is up to the performer himself to use initiative by experimenting to find the most suitable poundage. The advised reps, must be adhered to, however, and instructions of progression will be given in a later chapter.

This is a fine movement for strengthening the muscles that aid the bar in passing the sticking-point.

Take hold of the bar with the usual Press grip and SNATCH (not clean) it to arms' length. Use a split and recover immediately, bringing the feet in line and into the position usually adopted for pressing. Then, keeping the body upright, lower the weight slowly until if feels that if you allowed the bar to come any lower, it would at once sink to the shoulders. This usually occurs at eye-level, which is approximately the sticking-point in an ordinary Press. From here, without pausing, press the weight back to arms' length overhead.

4 sets of 4 reps with 30 lbs less than top pressing capacity.

The lifter will probably be familiar with the regulation dumbbells Press, and this exercise is very familiar for the most part except for the important detail of

the bells are held at the beginning.

of the hands to the front -- i.e., as a bar is held for "pulling in one hand clean" to the shoulder -- then take both bells from the floor to the shoulders so that they "lie" at he chest as they would do if a "curl" had been performed.

From here, press them alternately in the following manner: Press bell in the right hand and, as it passes the top of the head, turn the wrist so that the weight is in the usual position for the "one-arm military." Lower, and at the same time commence pressing with the left, carrying out similar action. The bells should pass at the halfway stage.

3 sets of 12 reps (6 with each hand). As the lifter may not be schooled in dumbbells lifting, no poundage can be advised, but I suggest one-half the performer's present limit barbell press as an experimental poundage to be divided equally between the two bells.

This is one of the few exercises which is not in itself an actual pressing movement, yet is distinctly helpful to the Press. It is a marvelous deltoid improver, and apart from being of service to the Olympic man as an aid to his press, should be in every body-builder's schedule.

Lie flat on the back with barbell at arms' length behind the head. (The exercise consists of nine separate movements that count as

From the commencing position of grasping the bar behind the head, proceed as follows:

1) Pull the bar over -- keeping arms straight -- until it is immediately above the face. Pause.

2) Lower -- resisting strongly all the time -- on to the thighs.

3) Sit up.

4) Still keeping arms stiff, raise bell into the "hold out in front" position.

5) Raise to arms' length overhead. Pause.

6) Lower steadily back to the thighs.

7) Lay back into supine position.

8) Raise bar back to position over face.

9) Lower slowly to starting position. Rest.

4 sets of 5 reps to commence, and trial poundage of 30 to 40 lbs.

All the movements in these four exercises should be performed at about the same speed as the lifter normally displays on a Press. No specially slow movements, but at the same time care must be taken not to employ any

Endeavor to do them rhythmically and smoothly throughout.

If the lifter is in the habit of using a thumbless grip, it is possible to do Exercises 1 and 2 with this grip. But although I use a "thumbless" in actual pressing, I believe it is advantageous to use an ordinary grip for all four movements.

I have already stated that the best method of improving the Press

is the Press in various forms. So it is with the second Olympic lift -- the Snatch. The various "Assistance Exercises" explained here have only one chief end in view; namely, the development of pulling power for the Snatch. The power of the pull and its

direction are the main attributes of good snatching, no matter what style is used.

When a lifter has developed a particular style that is favorable to him, he should train on this style

only. All experimenting should be done early in his career. It should be obvious that, in performing any movement, a lifter uses certain muscles more than others, and if he wishes to be proficient at any one special thing, he must develop these muscles albeit at the expense of others.

By this I mean that if a man has been snatching a certain way for, say, two years, he has put two years' work into developing his muscles to do that work. If he suddenly decides to alter his style -- even slightly, such as a wider grip, for instance -- a certain time must elapse before the muscles now being used are as good in quality as were those formerly employed. Any slight variation of movement brings different groups of muscles into action; or at least, exercises responsible muscles a different way. So it is obvious good sense to develop one good style and perform it constantly, so as to bring the muscles involved in this movement to their very best performance standard.

Of course, if the lifter suddenly realizes that his style

can be improved -- or is advised to this effect by a really qualified instructor -- it is up to him to make the necessary changes. But he must be prepared to see a reduction in his performances until such time as the muscles now brought into action become as proficient as were those formerly employed.

The above is my reason for disliking "hang" snatching as performed by most lifters. It is usual when performing this movement to do one snatch from the floor in customary fashion, then lower the bar, halting it with the discs about four to six inches from the floor, immediately from that point doing another snatch.

Now, when a lifter lowers the weight into this "near-floor-hang" position, he usually allows it to pull him forward; consequently, on the second attempt, two things occur that are detrimental. The first is that, by allowing the weight to be further forward than is usual, the lifter invariably pulls the second time with a

rounded back. The inevitable sequel is that the second pull cannot be in the same "groove" as his usual "all-the-way" pull. It is customary to do three or even four lifts from "hang" in this manner, it is obvious that a lifter so performing is putting in more practice

out of his usual "groove" than

in it. He is therefore not fully developing the muscles used in his "standard groove" style!

A better method of "hang" snatching is the one I have seen that wonderful snatcher, Julian Creus, perform -- also an original W.A. Pullum "Assistance Exercise. Instead of lowering the weight to the extent explained in the previous paragraph, he drops the weight on to his thighs and "re-sets" his back before pulling a second time.

Personally, I do

all my repetition snatches in training from the floor, and invariably in

single attempts. For the first couple of poundages (usual warming-up lifts), I use the "get-set" style, and do maybe three or four without releasing the bar,

but lower it to the ground each time. Then I do all my following reps, singly, using my usual approach to and "dive" for the bar. As I finish each attempt, I walk away, turn, proceeding immediately to my next, until I have completed my group for that weight. Then I rest, as usual, before taking my next poundage.

Exercise 5 -- Snatch without SplitThe "Assistance Exercise" I am describing first is one I use in my personal training, and have done for years. In fact, when I am on afternoon shift at work, I am forced to train at home and use this lift in place of the Snatch, as conditions make it impossible for me to employ a split. So competent has this made me in

pulling power that I have succeeded with 195 lb on various occasions.

Performance:

Adopting the usual starting position for snatching -- according to what attitude you favor in your stance to the bar -- the first part of the movement that follows is exactly as in the ordinary snatch. But when the bar reaches the point where the performer customarily splits, the pull must be prolonged to carry the weight overhead without moving the feet at all. In fact, to do the exercise correctly, the pull must be so lengthened as to carry the bar to arms' length

without a press-out! It will be impossible to avoid this press-out at first; but the lifter must endeavor to do this as little as possible, and try very hard to eradicate it altogether in time. This press-out makes the exercise easy and destroys a lot of its designed benefits.

Great attention must be paid to pulling the weight

back. Actually, I do not believe anyone does pull a

heavy weight back on the Snatch, but trying to do so automatically assists in preventing it

going forward.

This particular movement is a wonderful exercise for improving pulling power, and another point is this. The lifter becomes so addicted to pulling weights

high, he does this consistently when performing complete snatches with heavier weights. Of course, really heavy weights cannot be pulled head high; otherwise, they would

not be heavy. But in snatching, this principle definitely governs: The longer the pull, the easier the lift.

Remember to lower the bar to the floor after each attempt. Use the usual Snatch grip, and make it as near a real Snatch as possible without foot movements.

Some men may find that, in attempting to pull back, they raise slightly on the toes; a natural consequence, due to changing direction from the start in the path of travel. This in no way lessens the benefits derived.

Advised commencing reps and poundage:

4 sets of 4 reps, trial poundage of 50 lb.

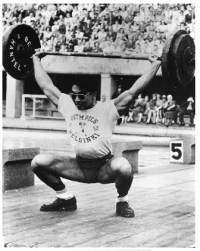

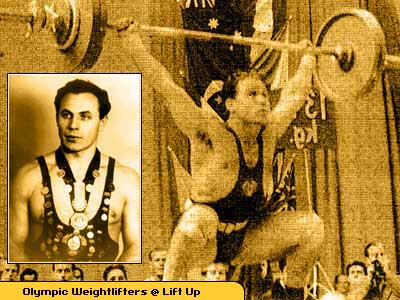

Exercise 6 -- Snatching from Two ChairsThis is another favorite exercise of mine, and is extremely useful in assisting a man to split low. As the title indicates, it is performed first of all be setting the bar so that the discs rest on two chairs. To bring bar to required height in most cases it will be found necessary that the chair supports should be built up so that, when the lifter grasps the bar, his arms, legs and back should be perfectly straight. In other words, he should be standing erect, bar grasped with arms completely locked at the elbows.

If the weight is fixed so that the bar is in a

lower position, it makes the movement much easier. This is only permissible at first if the lifter finds difficulty in performing the exercise correctly. But he should work away from this lower position as soon as ever he possibly can to the higher one which is really the absolutely essential position of the exercise.

From the position described, the lifter must make a concentrated effort to "wrench-pull" the bar upward. The high position renders any assistance from the legs impossible, the upper limbs and body being compelled to do all the work. When the pull had reached its fullest extent, the exercise is completed as an orthodox Snatch. That is to say, with splitting.

Due to receiving no initial help from the legs, the pull is obviously much limited; it will therefore be found necessary to split fairly wide to facilitate fixing the bar overhead. But as the weight, when it is actually at arms' length, will feel fairly light, relatively, recovery should not be difficult. In placing of the chairs, it is advised that their backs be turned away from you; so that, when the erect position has been reached at the conclusion of the lift, a pace back can be taken and the bell lowered without risk of damage to the chairs.

Advised commencing reps and poundage:

10 single attempts with approximately half your top snatching poundage.

Exercise 7 - Dead Hang Pull-UpThis is actually a variation of Exercise 5 proceeding to a combination of Exercises 5 and 6. Although less poundage is handled than in Exercise 5, effects are none the less strong, results produced being quite as positive because assistance from the legs is still kept out of the action.

Performance:

Take a barbell into the "hang" position, using the usual grip. This should find you braced well erect, bar held in front of the thighs.

Proceed from here --

without any preliminary dip of the body -- to wrench the bar to arms' length overhead exactly as in Exercise 5. Remember,

no foot movements -- and pull

back. But don't work the head and body forward as you pull back; otherwise you detrimentally interfere with the design of the exercise.

As it is a natural instinct to dip prior to the pull, great concentration must be exerted in endeavor

not to do this. If found impossible at first to perform as instructed, place the bar on two chairs [or boxes] and per the routine of Exercise 6. If this has to be done, it is a good plan to have these built up to a point where standing perfectly erect to "dead-hang wrench" takes the plates about an inch up from the supports. Then, if you are unconsciously inclined to bend a little at the knees when performing, you will receive notice of this by the plates dropping back to the supports. Knowledge of this helps appreciably to correct this error.

This is, again, a good movement for the man forced to do some of his training at home; moreover (like 5), it is a fine exercise to warm up on for the Snatch in usual training.

Advised commencing reps and poundage:

4 sets of 5 reps. Trial poundage of 50 or 60 lbs.

Exercise 8 - Rising Trestle Snatching (Progressive Starting Position Adjustment)This is an excellent exercise for all, and especially the man with a limited poundage at his disposal. The apparatus required is easily constructed by the handyman, and will very soon repay the lifter by improved performance. It consists of two trestles with solid bases. Overall, these should be the height of the man's hands in the "hang" position, and the sloping pieces should be notched on the one side every two inches, deep enough so that the bar can rest in them loosely. This is a "static poundage" exercise, most helpful for the man who is stuck at a certain weight, because by this method it is possible to progress beyond that weight, albeit slowly.

Commencing with a poundage that can be handled 10 times, snatch it

from the floor in the "get-set" position. When a suitable time has elapsed -- say, two weeks, training twice or three times each week,

doing 10 single reps only each session -- place the bar in the

lowest notch and again do 10 single reps each session. When suitable progress has been made -- which means when the 10 reps have become easier -- raise the bar another notch and similarly proceed. Eventually, if the lifter has been patient enough to make haste slowly, it will be possible for him to do the 10 reps from "dead-hang"; i.e., from the height of the highest position on the racks. When he has reached this stage of progression, the bar is made slightly heavier and returned to the floor as start for a similar rising routine.

This is

not an exercise for a month, but should be given at least a six-months' trial in conjunction with the usual training. It is, of course, possible to carry on indefinitely, and I myself in 1938 worked on this movement twice weekly, doing my other training three times weekly, for twelve months. During this time my Snatch improved 20 lbs.

In

all Snatch exercises, it is wise policy to carry out the movements as near to your own regular snatching style as possible. Make it a habit to perform this way, and then you find that instead of having to concentrate quite so much on

doing that style, you can use most of your mental powers to influence

pulling.

A good lifter only fails because the weight is too heavy for him. If you develop your style so that you can repose the fullest

confidence in it,

that's the only time

you will fail.

"Assistance Exercises for the Clean and Jerk"

In a previous chapter I have given my reasons for disliking the Dead Lift as an aid to cleaning, but if you personally like dead lifting, here is a variation that is much more beneficial to the Olympic man than when the lift is performed in the orthodox style.

Exercise 9 - Stiff-Legged Dead Lift from Box

Performance:

Get a block of box, nine to 12 inches high, and do your Dead Lift with straight legs. Do your first pull ordinarily from the floor, then lower the bar as you stand on your raised base so that it almost touches your toes -- and pull from there. By doing this you are actually pulling the bar from what would be floor level; and by keeping the legs straight you give more work to the back.

Advised commencing reps and poundage:

10 reps at any one session are ample. Trial poundage of about 40 lb less than your Clean.

Exercise 10 - Clean and Jerk Without Split

Performance:

Having adopted your usual cleaning position, viciously pull the bar as high as you possibly can, in addition, pulling back. As the pull finishes, turn the wrists and push up the elbows to fasten the weight at the shoulders.

It is possible that you may have to bend the knees at this stage, but as the whole idea of this exercise is to aid pulling power, it is best if you can perform the movement without dipping; in any case, never should you have to use more than a quarter-squat.

For the next part, use the dip as you normally do in jerking to get the weight away from the shoulders. As its poundage is relatively light for jerking, it should be possible to get it almost to arms' length with this initial heave. That, actually is the objective for this part of the lift: to get the bar to arms' length unassisted by foot movements. The lifter should be prepared, therefore, to push out strongly at the conclusion of the lift in case the jerk from the shoulders was insufficient to lock the elbows. On no account should the feet move -- neither should the legs bend again after the first dip.

This is a good exercise to practice the hook grip with, and to learn to change over to the ordinary grip as the weight comes in to the shoulders. This is done by sliding the thumbs out from under the fingers as the wrists turn over. It is quite a simple movement, and soon becomes habitual.

It is possible to do some exceptional poundages in this particular exercise lift, and I actually get to within 20 lb of my commencing match poundage on the Clean. It will be realized the good effect this has on a man's confidence! If he dies, say, 220 lb without split and a minimum dip of the body, 240 lb to commence with in a match comes easily. I am giving two separate advanced schedules for this exercise, as while one person may feel that it is his Clean which needs attention, with another it may be vice versa.

For the man who needs assistance on the Clean, I suggest the following, the reps being singles without releasing the bar (but allowing it to return to the floor after each attempt):

With 100 lb below limit Clean - 4 Cleans and 1 Jerk

With 90 lb below limit Clean - 3 Cleans and 1 Jerk

With 80 lb below limit Clean - 3 Cleans and 1 Jerk

With 70 lb below limit Clean - 2 Cleans and 1 Jerk

For the man needing help with the Jerk:

With 90 lb below limit Jerk - 2 Cleans and 3 Jerks

With 80 lb below limit Jerk - 2 Cleans and 3 Jerks

With 70 lb below limit Jerk - 1 Clean and 3 Jerks

With 60 lb below limit Jerk - 1 Clean and 2 Jerks

Exercise 11 - Seated Clean

This is a wonderful exercise for improving the Clean, but it is easily ruined as an exercise of special design by being performed wrongly. This is the way it should be done:

Performance:

Sit on a chair, box or bench that allows you to have both feet solidly on the floor. Then bend forward -- or should I say, lower yourself still seated -- to grasp the bar and, without raising the buttocks from the bench, pull the weight in to the shoulders. Assuredly to perform this exercise correctly, the following points must be noted:

You must pull whilst seated.

You must not rise up during the pull or when turning the wrists.

You must sit well back on the bench and not on the edge.

If you have difficulty in balancing, you may hook your feet round the bench legs, but this should not be necessary. You really must pull to bring the weight up high enough to turn the wrists over.

To recover, stand erect, weight at the shoulders. Then lower the bar back to the floor and re-seat yourself, ready for recommencement.

Advised commencing reps and poundage:

4 sets of 3 reps. Trial poundage with just over half maximum "cleaning" poundage.

Exercise 12 - Cleaning from Two Boxes

This exercise is exactly as Exercise 6 on the Snatch, except that it is performed with a Clean grip (i.e., hands not spread so wide apart as for snatching) and, of course, only pulled in to the shoulders.

Performance:

It must be remembered that the arms, legs and trunk are all kept straight. If the weight is fixed at the right height, this commencing attitude of the limbs and body will naturally result.

As in snatching from this position, no assistance whatsoever can be expected from the legs; it is therefore vital to use every possible available muscle left which acts in pulling. Again, too, a deep split [or squat] is essential (if a suitable weight is being used), but once at the shoulders, recovery is not difficult owing to the relatively light poundage involved.

To recover, step back once the weight is "in," lower to the "hang" and replace on the supports.

Advised commencing reps and poundage:

10 single reps. Trial poundage with two-thirds of maximum Clean and Jerk.

In execution of all the exercises in this chapter, it should never be the practice of the performer to try and make them easier by adopting any position that helps to do this; nor, for that matter should he just as mistakenly make them harder by doing them in a strained position. Even though some of them are unorthodox, therefore unusual, it is possible to do them comfortably and correctly. And in doing them this way, the lifter insures getting the best out of them, so getting the best out of himself.

Most probably the advised poundages will apply to very few readers. They are only given as a guide; and, as in lifting, one man will be able to perform some exercises better than others. It is up to the individual to use his own discretion in selecting the right poundages. Or, to make assurance doubly sure in this respect, place himself under the man who devises all these movements, the same as I did. I can guarantee that if he does this he will get genuine personal attention to his particular individual needs.

In order to aid the reader who may wish to use one or more of the schedules in which these exercises appear, I list them here for easy reference.

"Special Assistance Exercises"

1) The Seated Press

2) The Half Press

3) Alternate Press with Dumbbells

4) Combination Movement

5) Snatch without Split

6) Snatching from Two Supports

7) Dead-Hang Pull-Up

8) Trestle-Snatching

9) Stiff-Legged Dead Lift from Block

10) Clean and Jerk without Split

11) Seated Clean

12) Clean from Two Supports

"Explanation and Schedules"

When, many years ago, W. A. Pullum first originated "Assistance Exercises" and named them so appropriately, he was actuated mainly, if not entirely, by the strength motive. That is to say, he devised these movements with the idea of making himself much stronger than he was on certain lifts and feats, some parts of which resembled these movements or were exactly the same. The way he reasoned was that, where these lifts and feats had disclosed weaknesses in his make-up, the obvious way to remedy these weaknesses was by intensely practicing movements of the character which had revealed them. Best proof of the logic of this reasoning is furnished by his terrific later achievements as a champion weight-lifter and music-hall "strong man."

The practice of "Assistance Exercises," however, need not necessarily be confined to a greater strength-producing effort; they can quite easily be adapted to form a body-building program -- just as can the Olympic lifts themselves. It is only a question of method, and the basic principle of that method is very simple both to explain and understand. Briefly, to become stronger, one lifts heavy weights progressively a few times ("heavy" and "few" being comparative terms according to the established capacity of the person concerned). Principally to become better developed, one exercises with weights of lighter poundage a greater number of times ("lighter" and "greater" again being comparative terms in the same sense as before).

Dependent for full success, of course, on common-sense methods of application, the "Assistance Exercises" taught earlier in this chapter can be advantageously employed for various aims. They can be practiced as per original motive of design, viz., as builders of greater strength for already "style-proficient" Olympic performance; they can be beneficially employed as a "monotony break" if and when routine training threatens to become a grind; they can be made to serve as a base of technical education when the rudiments of style have still to be learned; and they can constitute the nucleus of a purely body-building program. In short, they can (I have found from experience) be beneficially used by everyone, beginner and expert. I am able, therefore, in all sincerity, to recommend them both to the ambitions Olympic aspirant

and his body-building colleague.

I now submit four specimen plans, each variously employing these exercises.

SCHEDULE 1 is mapped out primarily for the absolute beginner; to enable him to develop his muscles, suitably tone them up for progressive effort and, at the same time, obtain a grasp of style -- a requisite possession, in my opinion, if progressive effort is to be fully successful.

SCHEDULE 2 is for the body-builder-cum-Olympic man, who is interested equally in improving his physical appearance as well as his lifting totals.

SCHEDULE 3 is essentially for the man proceeding from body-building to a concentration on the Olympics.

SCHEDULE 4 can be of assistance to the man desiring a change from routine Olympic training; in fact, is specifically recommended for that purpose.

While it is not possible, in all honesty, to table poundages for any of these schedules (it is imagined that the reader will realize how ridiculous it would be to attempt to do so without personal knowledge of the performer), the set number of repetitions in each case should enable the weights to be individually fixed correctly.

To insure that full benefit is derived from the practice of these "plans," it is essential that the exercises are performed precisely in the order stated.

SCHEDULE 1

1st Exercise - Assistance Exercise 7 - Dead Hand Pull-Up

Commencing reps, first period: 4-4-4-4.

Progress as follows:

5*-4-4-4

5-5*-4-4

5-5-5*-4

5-5-5-5*

6*-5-5-5

6-6*-5-5

6-6-6*-5

6-6-6-6*

Then revert to the original 4-4-4-4 and add 2.5 lbs.

2nd Exercise - Assistance Exercise 1 - Seated Press

Commencing reps and progression same as above.

3rd Exercise - Assistance Exercise 10 - Clean and Jerk Without Split

Commencing reps: 8 single complete movements.

Progress to 10 single complete reps, then 12, after which add 5 lbs and revert to 8 reps.

4th Exercise - Assistance Exercise 9 - Stiff-Legged Dead Lift From Box

Commencing reps and progression as in previous exercise.

5th Exercise - Assistance Exercise 4 - Combination Movement

Commence with 10 reps and add 1/2 or 1 lb discs to the bar periodically.

N.B. The "starred" figures show how and when progression is effected. And similarly onwards.

SCHEDULE 2

1st Exercise - Assistance Exercise 5 - Snatch Without Split

Commencing reps: 4-4-4-4.

Progress as Assistance Exercise 7, Schedule 1.

2nd Exercise - Assistance Exercise 3 - Alternate Press with Dumbbells

Commencing reps: 8 each hand.

Progress to 10 reps, then 12, after which revert to 8 reps and add 2.5 lbs to each bell.

N.B. The reps can be performed in groups of 4s (or 5s) if desired.

3rd Exercise - Assistance Exercise 10 - Clean and Jerk Without Split

Commencing reps: 4 reps using maximum Press poundage

3 reps with 10 lbs added to bar

2 reps with 10 lbs added to bar

1 reps with final 10 lbs added to bar

Progression: Same poundages -

4-4*2-1

4-4-3*1

4-4-3-2*

Then revert to 4-3-2-1 and add 2.5 lbs throughout.

4th Exercise - Assistance Exercise 6 - Snatching from Two Supports

Commence with 8 single repetitions.

Progress to 10, then 12

After which, revert to 8 reps, adding 2.5 lbs.

5th Exercise - Assistance Exercise 9 - Stiff-Legged Dead Lift From Box

Commence with 8 single repetitions, as in previous exercise, and progress similarly.

6th Exercise - Assistance Exercise 1 - Seated Press

Commencing reps: 4-4-4-4

Progress as in Assistance Exercise 7 in Schedule 1.

SCHEDULE 3

1st Exercise - Assistance Exercise 3 - Alternate Press with Dumbbells

Perform 3 sets of 6 reps (3 each hand) and progress as follows:

8*6-6

6-8*6

8-8*6

6-6-8*

6-8*8

8*8-8

Then revert to 6-6-6 and add 2.5 lbs to each bell.

2nd Exercise - Assistance Exercise 5 - Snatch Without Split

Commencing reps: 3-3-3-3

Progress as follows:

4*3-3-3

4-4*3-3

3-3-4*3

3-3-4-4*

3-4*4-4

4*4-4-4

5*4-4-4

5-5*4-4

4-4-5*4

4-4-5-5*

4-5*5-5

5*5-5-5

Then revert to 3-3-3-3 and add 5 lbs to the bar.

3rd Exercise - Assistance Exercise 9 - Stiff-Legged Dead Lift from Box

Commence with 8 single complete movements.

Progress to 10 reps, then 12

After which, revert to 8 and add 5 lbs.

4th Exercise - Assistance Exercise 10 - Clean and Jerk Without Split

Commencing reps:

4 sets of 3 Cleans and 1 Jerk.

Use 1-lb discs periodically for progression.

5th Exercise - Assistance Exercise 1 - Seated Press

Commencing reps:

3-3-3-3

Progress as follows:

4*3-3-3

4-4*3-3

4-4-4*3

4-4-4-4*

Then revert to 3-3-3-3 and add 2.5 lbs to the bar.

SCHEDULE 4

1st Exercise - Assistance Exercise 1 - Seated Press

Commencing reps:

4-4-4-4

2nd Exercise - Assistance Exercise 6 - Snatch Without Split

Perform 10 single movements.

3rd Exercise - Assistance Exercise 10 - Clean and Jerk Without Split

Perform 4-3-2-1 with "assessed" poundages given in Schedule 2 for this exercise.

4th Exercise - Assistance Exercise 9 - Stiff-Legged Deadlift from Block

Perform 10 repetitions using moderately heavy weight.

5th Exercise - Assistance Exercise 3 - Alternate Press with Dumbbells

Perform 2 sets of 8 reps (4 each hand).

N.B. It will be observed that no system of progression is given for the above plan. Reason: As this schedule is intended for the man desiring a break or change from his usual routine, it is most probable that training on it will not be prolonged enough to call for this. Should, however, he consider that his condition warrants remaining on it longer than anticipated, he can do no better than employ the "miniature disc" system of progression throughout.