Last February (2006) Dave Draper’s wife, Laree, contacted me regarding an online forum about my book The Strongest Shall Survive. She asked if I’d respond to questions posted by members of the forum. Since I’ve never been one to pass up free publicity, I readily agreed.

Here:

Those of us who have been weight training for a wide variety of reasons for any length of time tend to change their focus as regularly as the seasons, so I wasn’t sure just what aspect of training the online participants would be interested in: rolling around on fat balls, kettlebells or perhaps some magical routine that would make them huge and strong by working out five minutes a day, twice a week.

So I was surprised that the majority of questions dealt with some aspect of the military, or overhead, press – how to do it correctly, why was it dropped from official competition, is it a safe lift to teach youngsters, is it “less traumatic” to the shoulders than the flat bench and is it a better exercise for athletes than the flat bench? In addition to the large number of inquiries from the online forum, I also received several letters that basically asked the same things. It seems that the military press has once again stepped out of the shadows and into the spotlight.

Which is where it belongs. Yet for a long time I was one of the few who encouraged everyone who lifted weights – bodybuilders, athletes, powerlifters, Olympic lifters and those who trained for overall strength fitness – to include the military press in their routines. I fully understood the value of being able to press heavy weights because I’d always pressed. As did everyone else in the gym regardless of why they were lifting. The two primary exercises that absolutely every person who was trying to get bigger and stronger did were full squats and military presses. No exceptions. The exercises selected for the back varied, but not for the upper and lower body.

The military press was the standard by which strength was gauged. “How much can you press?” was always the question asked when someone wanted to know how strong you were. The rite of passage was to be able to press your bodyweight. Once you achieved that feat, you were on your way. By the way, that’s still an excellent measure of upper-body strength. I’d be willing to bet that in a gym where several are benching in the high 300s or even in the 400s, not a single one of them can military press their bodyweight.

The shift in giving the bench press priority over the military press wasn’t gradual but quite abrupt. Strike one was when the press was eliminated from Olympic weightlifting competition in 1972. Strikes two and three quickly followed: the emergence of the sport of powerlifting, which used the bench press as the test of upper-body strength, and the explosion of weight training for athletes across the country, especially for football. The bench press prevailed because 1) more weight could be used, 2) it was easier to teach, and 3) it was deemed safer. The final reason was the most important of all. Coaches and athletic directors were often wary of students lifting weights and certainly didn’t want to increase the risk of injury by including an exercise that had been banned from the Olympics.

Youngsters and beginners were no longer introduced to the military press for fear it would cause lower-back injuries, a direct result of the International Olympic Weightlifting Committee’s declaration that the press was no longer a part of the sport because so many back injuries were occurring due to the nature of the new style of the lift.

So presses were suddenly harmful, not helpful. No one doubted that is such as austere, knowledgeable body as the International Weightlifting Committee considered the press dangerous, than it must be. In truth, the committee was made up of a group of self-serving old men who used the sport for personal gain and power, Bob Hoffman being a prime example. There was no medical evidence to support the contention that the military press caused injury to the lower back. That was the smokescreen. Dropping the press was purely a political decision and had nothing whatever to do with the health of the athletes.

The real reason that the press was no longer a part of the Olympic sport of weightlifting was simply that the judges had allowed it to get completely out of control. Who sat in the judging chairs determined whose lifts got passed, and in international contests, politics took precedence over fair rulings. Some lifters got away with excessive layback while competitors from other nations had to stay very erect or be disqualified. Some used an extreme knee kick that resembled a push press, but the lift was passed if the judges were friendly. Even when the lifter adhered to the rules strictly and didn’t lay back too far or knee-kick the start, the judges always had an ace in the hole – the bar stopping on the way up. Having the bar stop on the way up was not to the lifter’s advantage. Just the opposite – and it got a lot of presses red-lighted.

At the major international meets, it got downright ugly. At the ’68 Olympics in Mexico City I was standing off to the side of the stage, observing the technique of the foreign lifters. I watched two Caribbean judges give red lights to a lifter from Cuba on his first two attempts, even though his presses were flawless. His knees stayed locked at the start, he remained erect throughout the lift, and he never paused from beginning to end. The Cuban coaches ranted and raved, but to no avail. He got three white lights on his third attempt. It didn’t matter. The two judges had made sure he’d be out of medal contention. In meets at that level, one failed attempt is enough to lower a placing by five or six spots. While I had no love for the Cuban, I still thought the actions of the two judges were totally out of keeping with the spirit of the Olympic Games. That lifter had worked very hard to earn the right to compete for the highest honor in his sport and had been royally screwed because of his nationality. Sad to say, he wasn’t the only one.

Politics, not a concern for the lifter’s well-being, prompted the committee to remove the press from the contested lifts. Few, however, knew the truth, which meant the press was suddenly relegated to the role of an auxiliary exercise, if it was done at all. You might wonder whether some lifters hurt their backs because of the press. Of course: The press is the same as any other exercise. Use sloppy technique and you pay the price. Even so, far more dings and injuries were incurred on snatches, clean and jerks and front and back squats than from pressing.

Also keep in mind that lifters spent one-third of their training time on the press, even more than that if the lift was lagging behind. That meant three to four sessions a week where they hit the press hard and heavy. I’m not suggesting that anyone train for the press in such an extreme manner. When I insert military presses into people’s programs, I have them press only twice a week, and they go heavy just once during the week. I also make sure they learn proper technique before piling on the plates and do plenty of specific lower-back exercises to ensure that their lumbars can take the stress if they do lay back.

It’s extremely difficult to learn how to lay back when performing a military press. It takes a great deal of practice to lay back at the precise moment and do it smoothly. The military press is one of those exercises that’s easy to learn but tough to master. I can teach athletes how to snatch or clean and jerk faster than I can teach them the finer points of the military press. That’s why I allotted so much training time to it. Sure, there were a few who merely muscled the weights up, but having excellent technique upped the numbers appreciably. Naturally, I don’t recommend excessive layback, but in reality, that just doesn’t happen. So stress to the lower back really isn’t a problem.

Speaking of injuries, I can say with certainty that one type of injury prevalent today was unheard of when the military press was the primary upper-body exercise – damage to the rotator cuff muscles. We didn’t even realize there were such muscles. No one who pressed had any trouble with them simply because the exercise strengthened them. Rotator cuff injuries started occurring soon after the bench press replaced the military press as the main exercise for developing shoulder girdle strength. The bench press was overtrained to the extreme and usually done with sloppy form, since all that mattered were numbers.

At the same time, the part of the back that houses the rotator cuffs was neglected, so the weakest-link concept emerged, as it always does. You just can’t slide around a natural law. Walk into any commercial gym in the country, and you’ll find a half dozen people with rotator cuff problems. It’s become almost epidemic and isn’t likely to change in the immediate future. Whenever people approach me asking for advice concerning their rotator cuffs, I tell them to start doing military presses. If they’re very weak pressers, I have them use dumbells. As they gain strength in the movement, they graduate to the Olympic bar.

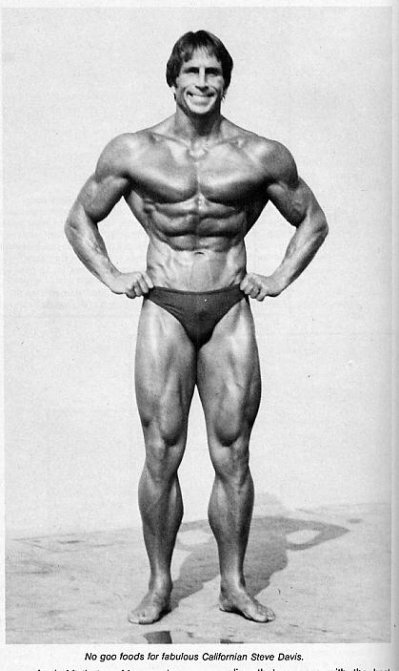

Keeping your rotator cuffs healthy is a real plus for the military press. There are other benefits as well, It’s one of the best – perhaps the best – exercises for developing the deltoids completely, whereas other upper-body exercises, such as the flat and incline bench press, neglect the lateral head. It’s a great movement for building strong, impressive triceps. All you have to do is look at photos of the great pressers of the ‘60s to verify that. Phil Grippaldi, Bill March, Norb Schemansky Ken Patera, Bob Bednarski and Ernie Pickett immediately come to mind. Their amazing triceps and shoulder development was a result of doing lots and lots of military presses, period.

Military presses become a part of the routines of all my athletes, both male and female, because the shoulder and back strength gained from handling heavy weights in that lift converts directly to every athletic endeavor, such as shooting and rebounding in basketball, throwing and hitting in baseball, firing a lacrosse ball at 100-plus miles per hour and hurling a shot into the next county. That’s not the case with the bench press. Too much benching causes the shoulders to tighten and limits the range of motion, an important consideration for athletes engaging in activities that require a great deal of flexibility in their shoulders.

When you spend ample time on learning how to press, and move yours up into the mid-200 range, you’ll discover that it has a very positive influence on all your other upper-body exercises.

One of the best things about the military press is that it can be done in a very limited space and with a minimum of equipment – a bar and some plates. For those who train at home alone, it has another advantage: You don’t need spotters. Should you fail to press a weight to lockout, al you have to do is lower it back to your shoulders and set it down to the floor or on the rack. Even in extreme situations where you lose your balance and have to dump the weights, it’s still far better than being pinned under a heavy weight on a flat bench.

Speaking of dumping weights, when there were only metal plates, it was taboo. It damaged the floor and sometimes bent the bar. It wasn’t even allowed in meets. The lifter had to lower the bar under control back to the platform. Dropping it was cause for disqualification. Bumper plates changed all that. Seldom do I see people lower the bar after finishing a press, clean, snatch or jerk. They simply dump the bar. They reason that not having to ease the weights back to the platform saves them some energy to use on the upcoming attempts.

I hadn’t thought that much about the practice until I read what Bill Clark wrote in his Journal. In part, he stated that the press is a tremendous builder of upper-body strength – the lower back, the entire shoulder girdle, plus the hips. Then he recommended using iron weights. “There would be no more dropping of the bar. A lifter would control the weight from overhead to the shoulders, to the waist, and to the floor. Thus working the negative resistance . . . more for the price of one effort.

Good advice, especially for beginners.

At first, I’m only going to present basic information on how to do the military press, sort of a primer. I’ll save the more detailed points of form for later in this article. After pressing for four or five weeks, you’ll be ready to hone your technique. In the second installment, I’ll also attempt to explain the rather complicated style of pressing the eventually prompted the Olympic Weightlifting Committee to drop the lift from competition. It’s not easy to learn, but you might want to take a crack at it. I’ll also include ways to incorporate the press in your overall upper-body routine and how to make it stronger.

Now for the basics. Grip the bar at shoulder width. If you extend your thumbs so they barely touch the smooth center of an Olympic bar, that’s usually right. Naturally, those with broad shoulders will need to grip the bar a bit wider, but don’t overdo it. You’ll know that you’ve found the ideal grip if your forearms are perfectly vertical. It provides maximum upward thrust.

Place your feet at shoulder width with toes pointed straight ahead. I see people in the gym pressing with one foot behind the other, almost like a split in the jerk. Wrong on two counts. It places uneven stress on the lower back and doesn’t let you grind through the sticking point. It’s a weak position from which to press.

Wear a belt. Not for safety, because if you use sloppy form over and over or haven’t bothered to strengthen your lumbars, the belt isn’t going to prevent you from getting hurt. Rather, it’s useful in that it provides feedback, particularly in regard to laying back, and it helps keep your lower back warm.

When learning how to press, clean the weights rather than taking a bar off the racks. Believe it or not, that makes the lift easier. And if your primary goal is a solid fitness base, clean and press each rep. It’s a perfect push-pull exercise. Most trainees, however, want to improve their pressing power. In that case, just clean the weight and proceed to do all your presses.

Rack the bar across your front deltoids, not your collarbone. Resting the bar across your clavicles is painful, and doing it repeatedly can result in bruising the bones. Not good. Simply elevate your entire shoulder girdle to provide a ledge on muscle to place the bar on. That will also put the bar in a stronger starting position than when it’s set lower.

Your elbows will be down and close to your body – not tucked in tightly but more close than away. Your wrists must be straight, not cocked; that’s most important. If you have trouble keeping them locked, tape or wrap them.

After cleaning the weight, grip the floor with your feet to establish a firm foundation, and then tighten your legs, hips, back, shoulders and arms. I mean rigidly tight. If any bodypart relaxes at all during the execution of the press, the outcome will be adversely affected.

Look straight ahead, and continue to do so throughout the lift. Don’t get into the habit of watching the bar travel upward, which will carry you out of the proper pressing position. While learning to press, drive the bar off your shoulders forcefully, yet in a controlled fashion. Explosive starts will come later. The controlled start will help you learn to press in the correct line, which is straight up, directly in front of your face. The bar should almost touch your nose.

As it climbs up past the top of your head, push your head through the gap you’ve created, and at the same time turn your elbows outward and guide the bar slightly backward. Not much, though, or it will force you to lose your balance. When the bar is locked out, it will be right over the back of your head. That places it in a very strong position over your spine, hips and legs.

Still staying tight, lower the bar back to your shoulders in a deliberate manner. Don’t let it crash down on you. That can damage your shoulders and it carries the bar out of the correct starting position. Make sure you tighten up again; then do the next rep. When the set is completed, follow Bill Clark’s sage advice and lower the bar back to your waist, then to the floor.

When learning the lift, take a deep breath before you drive the bar off your shoulders and another after it passes the sticking point or once you lock it out. While the weights are rather light, breathing isn’t that critical. I’ll get into how to breathe with heavy weights later.

With practice, you’ll find that there’s a rhythm to the press, and when you hit everything just right, the bar will float upward. It’s a fine sensation to press a heavy weight overhead, unlike any other exercise.

I mentioned that I have my athletes press twice a week, but when you’re in the process of learning the lift, it’s all right to press at every workout. Do 5 sets of 5, and go as heavy as you can. Pay attention to form, and after a few weeks you’ll be ready for a more advanced version of the military press – the European Olympic press.

If people are doing military presses as part of their overall fitness program and are not at all interested in going after a heavy single, then the guidelines I mentioned previously will suffice.

Should your goal be to press big numbers, however, then you must invest ample time in practicing this lift. When the press was part of Olympic weightlifting, athletes would spend at least one-third of their training time on it, not just to strengthen the muscles responsible for pressing the weight but also to hone the finer form points. In the end, the athlete who had better technique would move ahead in competition, since the press was done first, before the snatch and clean and jerk.

The military press has evolved over the years. Way, way back, weightlifting contest consisted of as many as a dozen tests of strength. The press was one of them, and it was done in ultra-strict fashion. Athletes had to start the press with their heels touching, and they had to stay absolutely erect throughout the lift. Leaning back was not permitted. If that wasn’t enough, they had to elevate the bar at the same speed at which the head judge raised his hand. That was indeed a pure form of the press.

Over the year the rules got more lax, especially in regard to back bend. Some lifters were capable of leaning back so far that they ended up finishing the lift with their backs horizontal to the platform. They were the exceptions, of course, since it’s not easy to lie that far back and maintain balance when handling a heavy weight. Plus, an excessive back bend can be harmful to the lumbars.

Then, in the early 1960s, the press changed from being a test of upper-body strength to an explosive quick lift. Those who adopted the new style of press could drive a bar from the shoulders to lockout in the blinking of an eye. A perfectly executed press moved as fast as a jerk. It was a revolution in Olympic weightlifting and resulted in world records being broken almost faster than they could be recorded. Somewhat ironically, it was the radical alteration of the press that ultimately resulted in its being dropped from the Olympic agenda.

The new form of press was called European style, but, in fact, it wasn’t a European who devised the more dynamic technique. It was an American: Tony Garcy, the middleweight champion from El Paso, Texas, who moved to York to teach and train. Tony had developed the new style and polished his technique to a fine degree by the time he lifted on an international stage. That’s where the European coaches and lifters saw the potential of the high-skill movement and instantly adopted it. By the mid-60s, 100 percent of the European lifters were using the new style so it became known as the European-style press.

The European lifters trained under tightly controlled conditions. If the coach said to use the new style of press, there weren’t any objections. In the United States things were quite different. For the most part lifters coached themselves, and only a few had the opportunity to see this style of pressing. An athlete either had to watch Tony train at the York Barbell Gym or attend a meet in which he competed – and Tony didn’t lift in a lot of meets. The quick press did spread across the country, but nowhere near as fast as it did in the rest of the world.

Eventually, it became known as the Olympic press, but I’ve always thought that it would have been fitting and proper to label it the Garcy-style press. In gymnastics they will name a certain innovative move after the athlete who did it first. Why not in weightlifting?

As you’ll understand when I spell out the technical points for the Olympic press, it takes a great deal of mental and physical effort to perform the movement correctly. That will help you appreciate just how much time and energy Tony spent developing it.

I should mention that if you can’t deal with frustration, you’ll be better off staying with the military press. On the other hand, if you like being challenged and enjoy testing your athleticism in the weight room, you’ll have fun learning the finer points of this lift. Those of us who had been doing press in the conventional way for a number of years had difficulty switching to the more dynamic style because it’s a totally different movement. With lots and lots of practice, though, most of us were able to become at least proficient on the Olympic press.

Here’s a review of the basic form points for the military press. Again, you can take the bar off the rack and press it, but you’ll find that you can use more weight if you clean it and then do your presses. I think that’s because the clean helps you get your body tighter than when you just take the bar from the rack.

A belt is a good idea. It keeps your back warm, and it gives you feedback during the lift, particularly in terms of how far you are laying back. Don’t be fooled into thinking the belt will protect you from injuries when using sloppy form. It won’t.

Your grip is right if your forearms remain vertical during the execution of the press. Be sure to wrap your thumbs around the bar. Don’t use a thumbless or false grip. Gripping the bar tightly gives you much better control, especially when the bar tries to run forward, which usually happens when the weights get really heavy. Set your feet at shoulder width, with the toes pointed straight ahead. Clean the bar and fix it across your front deltoids. Don’t let it rest on your collarbones. Elevate your entire shoulder girdle to provide a muscular ledge (think: chest up) and the bar should be ser right where your breastbone meets your collarbones.

Keep your elbows down and close to your lats. Your wrists must be straight, not cocked. Should you find that you have trouble keeping them locked while pressing, tape them or secure them with wraps. You’ll never press any amount of weight if your wrists move around during the lift. Your body should be vertical from feet to head, and your eyes should be forward. A common mistake many beginners make is to follow the bar’s upward movement with their eyes. Don’t do that because it carries your upper body out of a strong pressing position.

Before commencing the press, take a moment to tighten all the muscles of your body, starting with your feet and moving on up to your traps, shoulders and arms. Squeeze the bar until you feel your forearms, deltoids and upper arms almost cramping. Take a deep breath, and drive the bar straight up so that it almost touches your nose. As soon as the weight passes the top of your head, extend your head through that gap you’ve created, and at that same instant turn your elbows outward and guide the bar slightly backward. Not much though – just enough to keep your power base under the bar.

Here’s where the bar should be when you lock it out: Imagine a line being drawn from the back of your head directly upward. That’s where the bar should end up at the completion of the press, right over your spine and hips.

As soon as you lock out the bar, breathe. And don’t merely hold the bar overhead. Rather, push up against it forcefully and try to extend it even higher. That activates many more muscles in the upper back than when you just casually hold the bar at lockout. Hold that dynamic lockout for three to four seconds, take another breath, and then, in a controlled manner, lower the bar back to your shoulders. It’s important not to allow the bar to crash downward. It’s painful to your collarbones, and it carries the bar out of the ideal starting position. You can cushion the descending weights by bending your knees, but be sure to lock them before the nest rep. In this style of pressing, your knees will always be locked.

Make sure everything is right: feet, placement of the bar on your shoulders, body extremely tight, eyes straight ahead. Then take a breath and do the next rep. After you’ve completed all your reps on a set and have lowered the bar to your shoulders, don’t dump the weights to the floor even if you’re using rubber plates. Lower the bar from your shoulders to your waist, pause, and set it on the floor with a flat back. Always stay in control of the bar. The only time you’re allowed to drop a weight is when you miss an attempt.

There are many similarities between military and Olympic presses, as both lifts involve moving the bar from the shoulders to overhead. Yet there are several differences as well, and those are what changes pressing from a pure-strength feat to a high-skill lift.

Your grip, where the bar is placed on your shoulders, and head position are the same in both styles of pressing. Other than those points, the two are as different as day from night. The feet, for example, need to be set closer in the Olympic press and must be pointed forward. That’s necessary in order for you to shift your weight from the balls of your feet to your heels and back again to the balls instantaneously. The success of the lift depends completely on your ability to make that transition smoothly and quickly – actually, faster than quickly.

On the military press your elbows are positioned close to your body, but on the Olympic style they need to be squeezed against your lats. That forces the elbows to stay low and directly under your wrists. Keeping your wrists straight is even more critical on the Olympic press than it is on the military version, so much so that I think it’s a good idea always to tape them.

Set your eyes directly ahead, and never allow them to look up at the bar as it travels overhead. Tuck your chin down toward your chest, and keep it in that position until the bar reaches lockout. You’ll understand why that helps after you’ve done a few sets of Olympic presses.

The biggest change from the way you perform the Olympic press in contrast to the military press is your starting position. On the military press you’re basically erect at the start. On the Olympic press you need to get into position like this: Lock your legs, tighten your glutes and abs, and extend your midsection forward until it’s over your toes. You want to create a muscular bow that starts at your heels, runs up through your legs, hips, midsection, back and shoulders and ends at the base of your head (see illustration).

You are, in effect, a coiled spring, with your weight on the balls of your feet. They form the base from which the lift is executed, and if that base is not solid, pressing a heavy weight will not happen. At York we used the analogy of trying to grip the platform with out toes much like a bird grips a limb of a tree. That helped us lock into the platform.

A powerful start is critical for success once the weights approach your best. The power for the start is generated out of the hips and legs, and transferred up through the midsection, back, shoulders and arms into the bar. Much of the explosive thrust comes from your lats and traps, although few think of those muscle groups in connection with pressing a weight overhead.

When utilized, the lats, along with the deltoids, propel the bar off the shoulders. Then the traps help elevate it even higher. In order for the start to be effective, it must be explosive. I liken it to a short jab in boxing, where all the energy is concentrated in a dynamic move. And, of course, the bar must be driven into a precise line. That only comes with lots of practice.

Once you put a jolt into the bar, transfer your weight back to your heels as you shrug your traps and extend your body vertically. At the conclusion of the start portion of the lift, your body should be perfectly erect.

Now comes the hardest part to master. As soon as you drive the bar as high as possible, you must shift your weight back to the balls of your feet and drop back into your original starting position, bowing from heels to head. At the same time you must continue to keep pressure on the moving bar. Otherwise, it will pause or even drop, and you don’t want that to happen, as it’s often impossible to set it in motion again. Pressing the bar upward as you resume the coiled position also helps you control the line of the bar. If you relax tension on the moving bar, it will invariably run forward, and it moves too far out front, you won’t have enough leverage to finish the lift.

As the weights climb upward, bring your hips back so they stay under the bar. Extend the bar on to lockout, where it is fixed directly over the back of your head. Control it and push up against it while you hold it for several seconds. Lower it to your shoulders in the same manner as I suggested for the military press, reset and proceed with the next rep.

After you have tried a few of these, you will recognize that they are nothing at all like a conventional press. One of the biggest differences is the balance factor. On a military press the bar moves slowly enough that lifters can usually manage to keep their balance, even with heavy weights, but the Olympic press consists of an explosive start, a quick move through the middle and a fast finish, with the bodyweight being shifted from front to back to front in a flash. Plus, the foot stance is narrower, which adds to the problem of maintaining balance through the Olympic press.

Those who used this style in the ‘60s and ‘70s will notice that I haven’t mentioned the key form point of the Olympic press – bending the knees at the start. You may be thinking, wasn’t bending the knees illegal? Yes, it was. The knees had to remain locked from start to finish. So how did the lifters get away with it? This is what Garcy figured out.

As soon as the bar was cleaned, the lifter quickly assumed his set position and waited for the signal to press. But he didn’t lock his knees tightly; he bent them just a bit. Why couldn’t the judges see that? Because it’s impossible to determine whether the knees are fully locked or not quite locked. Keep in mind that most Olympic lifters had massive thigh development, with quads that lapped down over the knees in some cases. If that sounds farfetched, stand in front of a full-length mirror and put yourself in that bowed starting position. Lock your knees. Now relax them just a fraction. They still appear to be locked. The only way you can tell they aren’t completely locked is if you saw them in the locked position before you bent them. And that never happened. Lifters knew how to get into the starting position without ever locking their knees. The only time the knee bend was noticeable was when a lifter dipped lower during the start. Sometimes that move was missed because it happened so fast.

That slight bend helped. When the lifter got the signal to press, he locked his knees as he hurled the bar off his shoulders. It may not seem like much, but the move provided enough extra thrust to drive the bar higher and with more velocity, and if the rest of the lift was done with precision, it helped elevate the numbers appreciably. Some contended it added as much as 40 pounds to their presses.

Of course, the new style drove officials crazy. Since they couldn’t see the slight knee bend, they had to give lifters the benefit of the doubt. And lifters performed the new press so fast, it was also difficult to tell how far they had leaned backward. Those who mastered this technique included Garcy, Tommy Kono, Joe Puleo, Fred Lowe, Bob Hise, Tommy Suggs, Ernie Pickett, Joe Dube, Bob Bednarski and Ken Patera, who blasted the bar from shoulders to lockout so fast that the lift was only a blur.

Because it is difficult to learn, I only teach the Olympic press to athletes who are advanced and are very athletic. Except for rare cases I have them lock their knees at the start. That helps simplify the lift and is still productive.

Before you try learning the Olympic press, with locked or bent knees, make sure your midsection, lumbars and abs are up to the task. Those muscle groups are put under lots of stress with the coiled start and quick return to that position. Be sure to always do warmups for your abs and lower back prior to pressing, and while learning the finer points of the Olympic press, stay with light weights. Remember the weightlifting adage: If you can’t use perfect form with a light weight, you’re not going to have it with heavy poundages. Since this is a high-skill movement, stay with 3 reps so you can concentrate on all the form points. You’ll find that Olympic presses are quite taxing mentally, which I think is a plus. Improving the nervous system while gaining strength sounds good to me.

Finally, a word about breathing on Olympic and military presses. When you use light weights, it doesn’t matter how you breathe, but when you’re attempting to move heavy triples, doubles or singles, it matters a lot. Take a breath just before you start the press and hold it until you have driven the bar past the sticking point or after you lock it out. If you inhale or exhale while pressing, your diaphragm is forced to relax, which creates a negative intrathoracic pressure. In other words, breathing during the lift diminishes your ability to apply force to the bar.

In that regard, be aware of the phenomenon known as the Valsalva maneuver because it occurs most often in the performance of a heavy press. When lifters hold their breath for too long during a maximum exertion, they hinder the return of venous blood from the brain to the heart. That can result in a lifter’s blacking out, which can be dangerous when you’re holding a loaded barbell overhead. Should you start feeling dizzy while trying to grind a press through the sticking point, lower the bar to the floor and go down on one knee. Don’t move around. Most injuries happen when athletes fall into a weight rack or another piece of equipment.